I grew up in a simpler time; despite living in New York City, it was a time of childhood adventure and freedom, that golden age before the disappearance of Etan Patz. Oh, sure, Times Square was seedy and Needle Park marred the Upper West Side but overall, the city was quite safe; my sister and I could play hopscotch on the sidewalk unmolested and walk to the park or Alexander’s without drawing unwanted attention from anyone. Not only could we go places alone, my parents – particularly my mother – encouraged it. We lived in a city, a great city full of artistic and musical resources, and she expected us to use it.

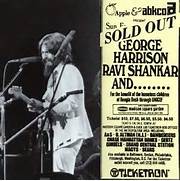

When I was twelve, George Harrison’s Concert for Bangladesh rolled into Madison Square Garden. It was an all-star lineup – the first I had ever seen – joining to raise money for a cause, in this case to counteract the effects of a famine in a country I doubt I could have found on a map then: it was truly ahead of its time, the precursor for No Nukes, Live Aid, Farm Aid, and countless others. I had heard about the show from Pete Fornatale, Scott Muni, and the other deejays on powerhouse WNEW-FM, arguably the most influential of AOR stations. It didn’t matter what it was for, anyway; the lineup boasted George Harrison, Eric Clapton, Billy Preston, Bob Dylan, and- my favorite – Leon Russell, among others and my best friend, Kim Brennan, and I wanted to go. The Garden was a bus ride downtown and a world away and all I needed was parental permission.

The two shows were scheduled for August 1, 1971, at 2:30 and 8 PM. Tickets were only about $8 and had gone on sale in July. Deciding that the afternoon show was more likely to elicit parental approval than the 8 pm one, Kim and I stood in line at the crowded box office. According to the sign, tickets were limited to four per buyer, so Kim and I decided to purchase that number, just in case an older sibling or two were sent along with us as chaperones. By the time we reached the front of the line, however, demand had caused the limit to change and each buyer was permitted only two. At this we grew frantic (it had not occurred to us that, as two people, we could still buy four) and we wondered how we could be certain our parents would permit us to attend unaccompanied. We handed over our crumpled singles and quarters and pocketed the tickets, the thrill of possession only slightly dampened by the cold realization that we might not be able to go.

As the ensuing weeks passed, Kim and I attempted to come up with a foolproof argument for why our parents should allow two middle-schoolers to attend a smoky, druggy, rock concert alone. ‘Everybody was going’ never worked with my parents, although it tended to persuade hers, probably because they were a few years younger than mine. The fact that it was for charity might sway my mom, although my dad was more likely to offer to write a check and tell me to go watch Million Dollar Movie and do my homework. As the day grew nearer and neither of us broached the subject with either set of parents, the situation began to seem hopeless. We feared they wouldn’t let us go see the show and we’d be out all of our pocket money and have missed seeing Eric Clapton and Leon Russell.

I thought I would sound out my mother the Saturday before the show as I helped her make dinner but she was preoccupied and grumpy over something stupid that my older sister had done, although her specific transgression is long lost into the mists of time. Whatever it was had infuriated my parents, though, prompting my father to go to his office that afternoon and my mom to spend the day in the kitchen slamming things. Dinner was silent and tense with my parents steaming and my sister sulking.

“Well, this is great,” I thought as I scrubbed the pots alone after dinner, my sister having repaired to her room with as much dignity as she could muster. “They are already furious about one kid. I can just hear it when I announce that I already bought the ticket.”

When I had finished in the kitchen I lifted the kitchen receiver gently and dialed Kim’s number. “Did you ask yet?” I whispered.

“No,” she hissed back. “Now isn’t a good time. My idiot little brother got caught shoplifting a Matchbox car at Woolworth’s and they are furious.”

Amazed at the universal stupidity of siblings, I sighed, “Yeah, here, too, only it’s my sister and it’s not a Matchbox car. Whatever it is is so bad they aren’t even saying.”

Kim sighed, too. “Well, tomorrow morning is our last chance,” she observed hanging up.

I was so depressed I went to bed at 8 pm with an Agatha Christie, cursing my luck, my sister, Kim’s brother, and my impending financial and artistic poverty.

Sunday morning I rose early, and, unasked, set the table for breakfast and cleaned up afterward. I dressed nicely for Sunday School and church and was ready early. Nobody noticed, though; both parents were angry about and preoccupied with my sister’s transgression. Just as we were about to leave for Fifth Avenue Presbyterian, I turned to my mom.

Taking a deep breath I blurted, “Can I go see the Concert for Bangladesh at Madison Square Garden today?”

My mother looked up from shoving Kleenex into her handbag. “With who?”

“Kim Brennan.”

She shrugged and returned to her task. “You know where the bus stop is.”

My father looked up from where he had been wiping the toes of his brogues with his handkerchief, a habit that made my mom furious. “Wait a minute. You think she’s old enough to go to the Garden on her own?”

My mother’s brown eyes bored into my father’s blue ones. “She won’t be alone; she is going with Kim. And I seem to have raised one child who can’t look after herself; I’ll be damned if I raise another one.”

They stared at one another for a minute then my father said, “At least call Kim’s parents and make sure it’s all right with them.”

My mom did. We went to church. Soon after we arrived home Kim’s dad dropped her at our house. My mom walked us to the bus stop and waited until the bus arrived.

“You have your tickets?” she asked as it pulled toward us and sighed to a stop.

“Yes,” we answered in unison, holding them aloft, crushed and sweaty.

“You know which bus to take home?”

“Yes.” We both nodded.

“You have money to call if anything goes wrong?”

“Yes.” We continued bobbing our heads affirmatively.

“Okay, have fun.”

The bus driver closed the door and off we went to one of the most amazing experiences of my young life. The show was great. Afterward, we called Kim’s dad from a pay phone booth and told him that we were going to the bus stop for the ride home, which we did. No one bothered us; no one even spoke to us. Kim’s dad was waiting at our corner when we exited the bus.

Years later, I met Eric Clapton at the Chelsea Arts Club in London and told him the story. He roared with laughter. “You had pretty progressive parents.” Now, as an adult, looking back on that day, I realized that he was right; I did. And at least as cool as the concert was – and it was a cool concert – is the thought that our parents trusted us, trusted the other concertgoers, and trusted New York. That is priceless.

I love this one! I’ll print and mail to Gma tomorrow…she’ll love it. xoxo

Sent from my iPhone

>

LikeLike

Thank you. She said you sent her a few.

XOXOXO

Sent from my iPhone

>

LikeLike